South Africa is transitioning into a new phase in the electricity supply industry with the move to a more competitive market. In this transition the need to maintain the dispatchable, baseload, low carbon capacity is also coming to the fore as increasing real world experience is showing the limits on Renewable Electricity production – even when supported by Battery Energy Storage Systems. This has been highlighted by the recent blackout in Spain.

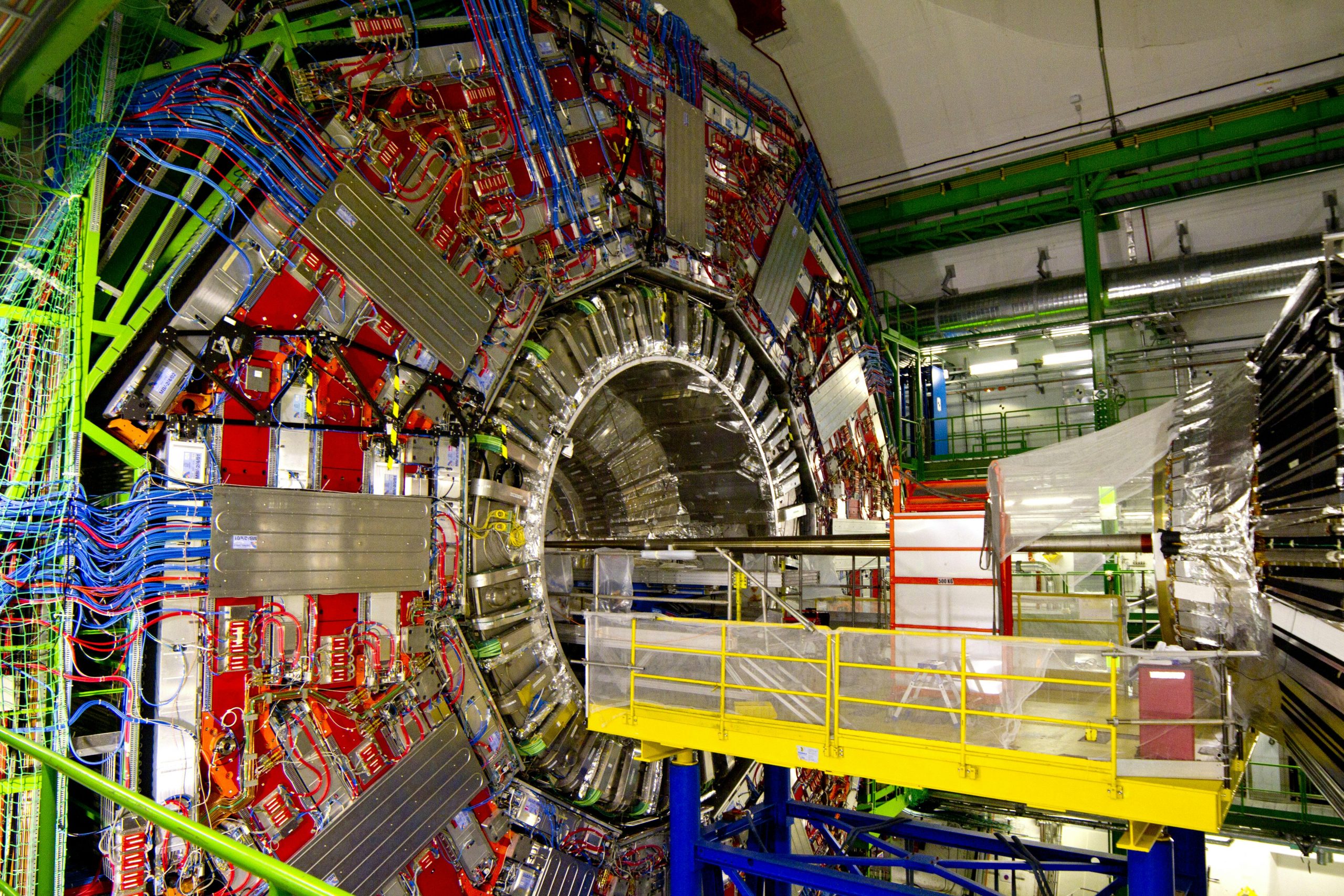

In this environment there appears to be increasing support for nuclear as a part of the long-term energy mix in the country. This has been emphasised by statements from both the Minister of Electricity and Energy as well as the senior Eskom Executives. The question is therefore how such a deployment would be done and whether it would be based on the current established technology of large Pressurised Water Reactors (PWR) similar to the existing Koeberg units or Small Modular Reactors (SMR) of a new technology and much smaller size (possibly 100MW class SMRs compared to 1000MW class PWRs).

South Africa has a long history in the nuclear energy field. The first reactor was the Safari-1 reactor which started up in 1965 and is still in full use to create radio-pharmaceuticals on a commercial basis, currently having some 20% of the world market. This was followed by the Koeberg nuclear power station with contract placed in 1976 and first unit starting up in 1984. It has operated successfully for over 40 years and has, in line with international practice, had life-extension work to keep it in service until at least 2044.

South Africa also led the world’s move towards SMRs with the PBMR project and, while the project was suspended in 2010, a large experience base remains in South African hands.

In terms of actual regulatory approvals there has been significant progress for PWRs with the recent final approval of the Environmental Impact Assessment for another 4000MW on the same site as the current Koeberg Nuclear Power Station. The approval of the Thyspunt site in the Eastern Cape as a potential nuclear site by the National Nuclear Regulator is under assessment (a Nuclear Installation Site License – NISL).

So what would be the motivation for proceeding with a PWR build programme? The main reason is that the PWR technology is very well established with several very credible designs in construction across the world and available on a “turnkey” contract basis with fixed tender prices. The overall costs of running such PWRs are clearly fully understood.

In terms of contracting for such a PWR programme there are well established and successful construction companies (or consortiums) that have exported reactors under a turnkey contract to several countries. They have also normally provided low cost concessional loans over extended time periods (normally 18 years after plant commissioning).

The first challenge that impact the PWR option is the size of each unit leading to high initial commitment, both in terms of grid impact and finance. The other major challenge is the difficulty in establishing a local supply chain for much of the major components. There would need to be a committed and sustained construction programme to justify local production of the high value items.

So what would be the motivation for proceeding with a SMR build programme? The basis of the SMR projects are to exploit small unit size (nominally between 30MW and 300MW) using different technical approach to the “classic” PWRs. This leads to a lower financial exposure for each unit as well, easier integration into the grid system and potential faster construction. Some of the technologies being proposed also lead to more flexible operation (load following).

The economics of SMRs depends on the scale of production and strict standardisation. If one is building 2000MW with PWRs that could be two units, so there is not much “learning” in the programme but if it was using 100MWSMRs there would be 20 units -leading to significant “learning”. This is one of the reasons why the Chinese, Russian and South Korean programmes with their standardised PWR designs have costs of about $2,000/kW whereas the First OfA Class (FOAK) costs in Europe and the USA have been about $10,000/kW. Clearly the scale of serial construction of these countries would be challenging for PWRs in South Africa but could be credible for an SMR programme.

Another significant benefit of an SMR programme would be a greater potential to localise construction of the plants because there is not an established supply chain for the components and the production volumes will be higher (of smaller components). If South Africa could be an early mover in the SMR field (to pick up where the PBMR left off?) it would place us in a highly competitive position to be a supplier to the rest of Africa, whose grids cannot support large electrical generation units, such as current PWRs.

Of course, the main challenge with an SMR programme would be the lack of maturity of the designs available. Unlike the PWRs there are only studies on the possible operating costs and the first units would have significant construction risks. It would therefore be logical to consider the few designs that have either been constructed and are in operation or are, a least, in construction. The cost and schedule risks on a fully unproven design would be severe.

So what would be the realistic timescale of a PWR or SMR programme. In the case of a PWR programme it could be expected to take two years from the final decision to launch a procurement programme to the final contract signature. From contract to completion of construction is reasonably eight years. Sensibly therefore from commitment to power is, at best, ten years. That is for the first unit and subsequent units are normally spaced at 12 months on each site. It can be shorter and the spacing of the units under Eskom’s Nuclear-1 proposed contracts in 2008 was six months.

In terms of an SMR programme the timescale is much more variable. If the design chosen had not yet been constructed in the country of origin the schedule would be very uncertain. There are, however, SMR designs that a currently in operation in China and Russia and others that are in physical construction. If one of these was selected then credible construction schedule of five years could be possible. Even if such a design was selected progress with the first South African unit would need to be demonstrated before clear commitment to a large scale roll out could reasonably be made.

Funding remains one of the key issues with any nuclear construction programme. For the PWR option the loans for the construction is normally supplied by the vendor country under concessional terms. These normally are about 4% nominal interest (or 2% real interest) in US Dollars or Euros with repayment over 18 years post plant startup (so called OECD rule).

For the SMR option it could be done as a joint venture with the vendor. This JV could become the supplier to South African and, ideally, the rest of Africa. The first unit, with all the FOAK costs, would clearly not be commercially competitive on the South African grid but could be funded by a “developmental” PPA, similar to that granted to Bid Window 1, 2 & 3 for REIPPP. As with the REIPPP the performance risk would be taken by the vendor/owner.

So what could be a reasonable way forward? If one uses the 2500MW in the IRP as a reference then there could be 2 PWRs constructed (at the Koeberg site?) and a SMR as a lead unit. Assuming both programmes met their objectives the PWR programme would continue providing the coastal support the national grid needs. Probably further units at Koeberg for the Western Cape, units at Thyspunt to support the Eastern Cape and, possibly, units at a site on the KZN/EC border to feed into KZN from the south.

The SMR programme would ideally expand on the existing Eskom coal sites to replace the baseload power from the coal stations using the same grid connections as well as supporting local communities. The SMRs could be used by the large municipalities to reduce their dependence on Eskom as well as large industrial plants, for both electricity and process heat.

Clearly if one of the programmes does not meet it objectives it would not be pursued beyond the initial build and its functions taken over by the other. One could use the PWRs on the existing Eskom sites or SMRs on coastal sites.